The murder of six Asian women in the Atlanta area on March 16 is a tragic reminder of how far we have yet to go to address the depths of racism.Though the motives of the alleged shooter have yet to be fully determined, there is no question that the mass shooting in Atlanta aligns with the surge of anti-Asian violence in the past year. The group Stop AAPI Hate reported that it has received 3,795 reports of anti-Asian verbal harassment and physical attacks since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. Resentment, anger and hatred towards Asians has been tied to racist rhetoric that scapegoats China for the coronavirus, branding it the “Kung flu” or the “China Virus.”

While shocking and disturbing, sadly the Atlanta killings are just the latest in a long history of violence against Asians that dates to the early arrival of Chinese immigrants in the 1850’s. Often in the context of economic competition and tensions between Asian and white workers, racism and nativism inspired discriminatory legislation and fueled mob violence. In 1882, for example under the rallying cry of “The Chinese Must Go!” the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. This was the first law to restrict immigration of a specified racial group. Later in 1885, white miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming, violently attacked Chinese miners who were perceived to be taking their jobs. Twenty-eight Chinese were murdered, 15 others were injured, and 78 Chinese homes were destroyed.

The city of Redlands did not escape the historical climate of hatred toward Asians.* In the 1880’s, Chinese immigrants came to the relatively new town of Redlands looking for work after completing the San Timoteo canyon railway line. They worked as domestic workers, gardeners, laundrymen and laborers. Some of the curbs, roads, and fountains we see today in the city were made by Chinese immigrants. The economic crisis of 1893, however, heightened tensions between white workers and the community of about 200 Chinese in Redlands. In August 1893, a crowd of 400-600 people gathered in protest against Chinese who were accused of causing white unemployment. A portion of the crowd broke off and marched to Chinatown. Banging on doors and windows, they demanded that the Chinese leave town.

City leaders, worried that the reputation of Redlands as a second home for wealthy easterners would be damaged, managed to stave off further violence. But this did not eliminate the drive to rid the city of Chinese. Using a section of the 1892 Geary Act, which had extended the Chinese Exclusion Law for another 10 years, city leaders required Chinese to go through a costly and time-consuming process of obtaining a Certificate of Residence to show they were authorized to be in the country. After arresting 7 Chinese for failing to comply with the Geary Act many of the remaining Chinese fled the city.

The Atlanta murders, then, are not isolated incidents, but follow a pattern of anti-Asian hatred and violence that now spans 170 years; a history that is often obscured by the invisibility of Asians or by the mistaken idea that Asian American “success” shields them from racism. Moreover, we must see the Atlanta killings through the lens of both racism and sexism. Longstanding, distorted stereotypes of Asian women as hypersexual, exotic and submissive leave them vulnerable to unwanted sexual advances, harassment and violence. These stereotypes are tied to a history of US servicemen soliciting sex workers while stationed on military bases in the Philippines, Korea, Vietnam, and Okinawa. Speaking out against what happened in Atlanta, then, requires standing against racism and sexism.

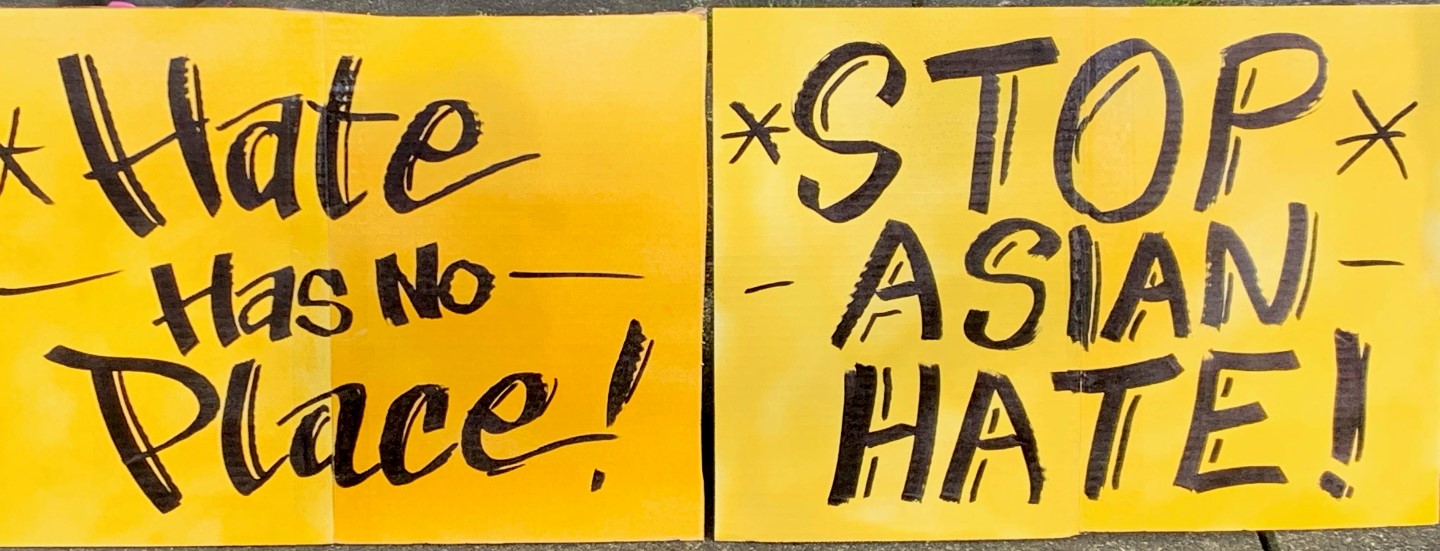

While the Atlanta killings have sparked justifiable outrage, the real tragedy would be if our outrage is short-lived and dissipates when the news cycle inevitably moves to another story. To avoid this, we call upon all members of the University community to commit to learning about and taking action to fight racism and sexism against Asian and Pacific Islanders. This can mean:

- Expanding the scope of our diversity, equity and inclusion work to bring visibility to the API experience.

- Supporting faculty to develop curricular offerings that deepen knowledge about the API experience.

- Expanding efforts to increase the numbers of API students and to support them while they are here.

*From “The Story of Redlands’ Chinatown,” Redlands Daily Facts, July 26, 2008, https://www.redlandsdailyfacts.com/2008/07/26/story-of-redlands-chinatown/

This statement is supported by members of the following caucuses and associations:

- Faculty of Color Caucus

- Asian Students Association

- University Council on Inclusiveness and Community (UCIC)

- Black Student, Faculty, Staff, Administrator, and Alumni Association

In light of recent events, members of the Faculty of Color Caucus issued this statement to communicate continued efforts to center collective work in the University of Redlands community with love and compassion. Thank you to Keith Osajima for leading the efforts in drafting this statement. The group’s co-conveners are Professors Nicol Howard and Maria L. Muñoz.